Alice Schivardi’s solo show is the first in a series of three—When thread, color, and word intertwine—curated by Giovanna Dalla Chiesa, which brings together the work of three artists: Alice Schivardi, Luciana Pretta, and Luisa Lanarca.

The exhibition features a selection of works that reflect Alice Schivardi’s distinctive language, her interest in intimate storytelling, and the creation of connections through drawing and embroidery.

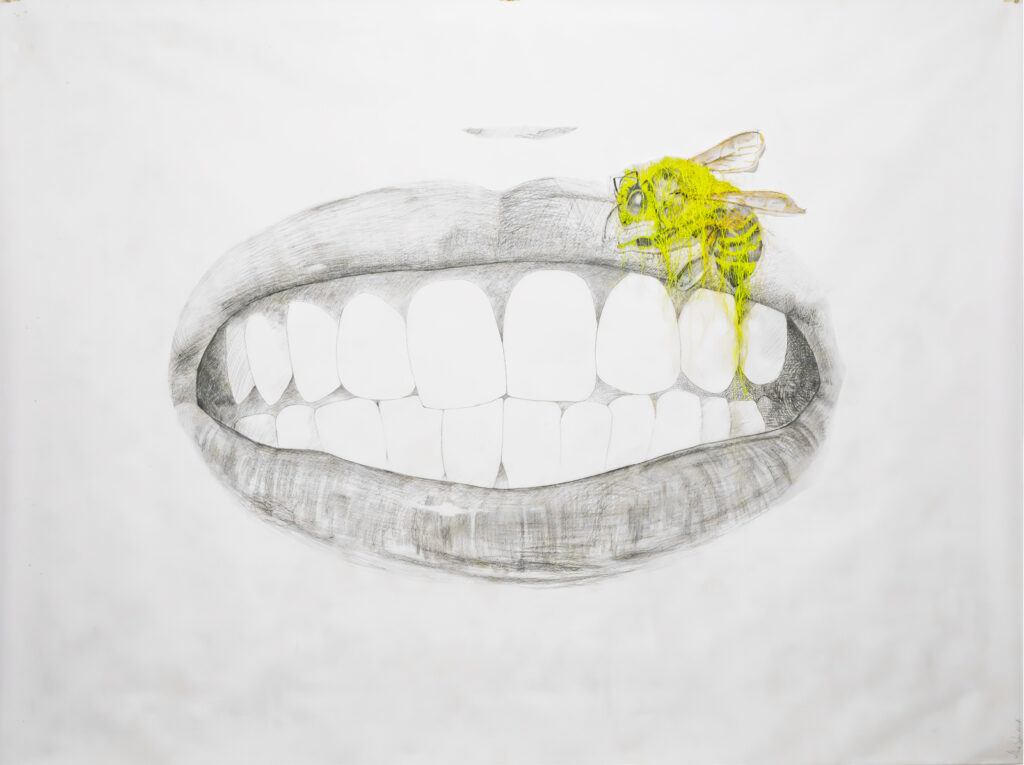

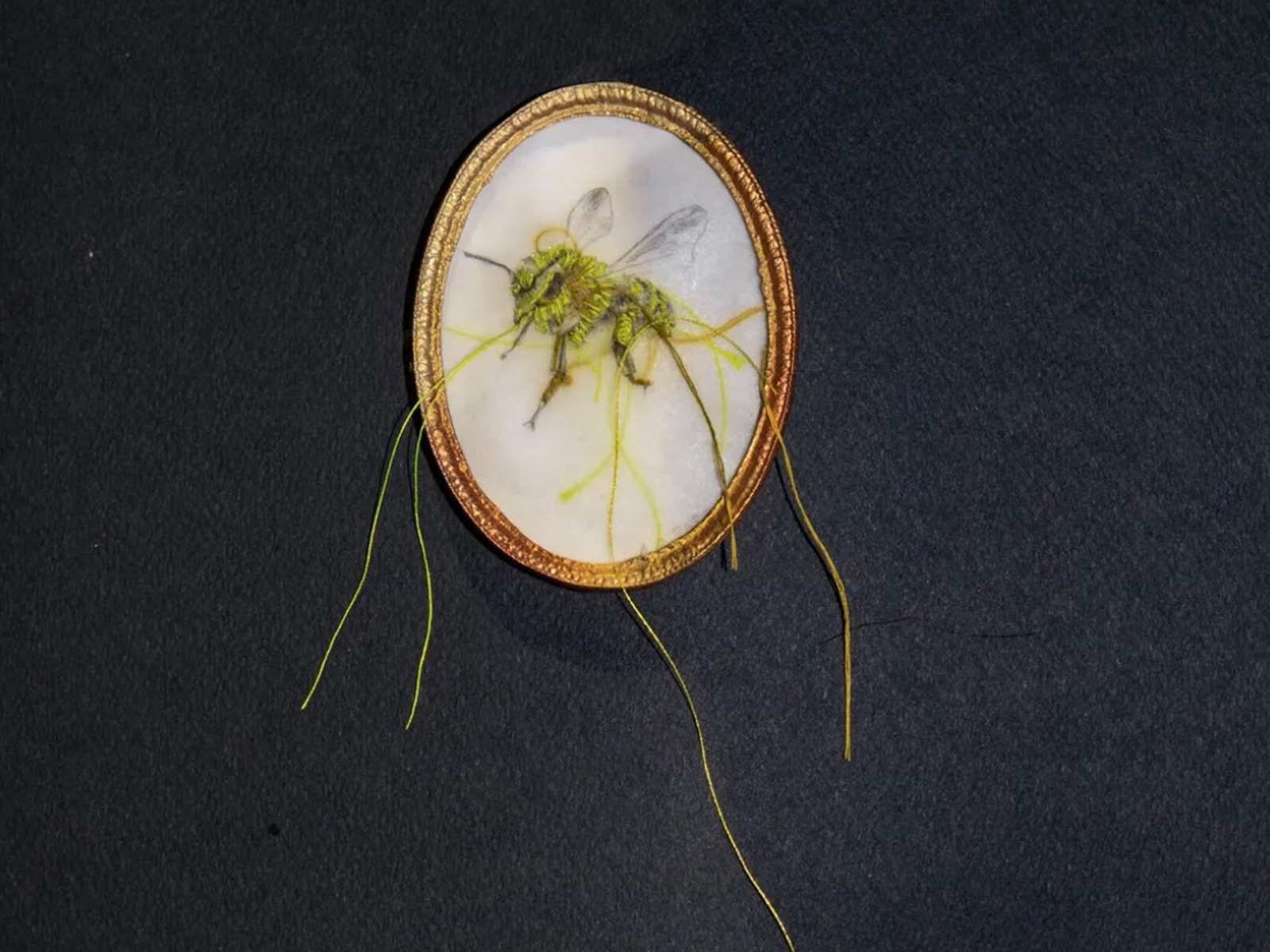

The display includes “Coccinelle” (2010-2015), an installation made up of 32 embroidered ovals on tracing paper, framed in resin, which together form a mosaic of hidden memories and emotions. From the series “Unconditional Love” and “Black Series”, two embroidered works on tracing paper, in which the thread becomes a tool to explore the depths of affection and human relationships. In “Echo of Light”, a bee lands on a mouth, imbuing the tension between silence and the need for speech with symbolic and anthropological significance. Lastly, a group of bees in flight (embroidery drawings on tracing paper, pencil, cotton thread, metal frame): each one traces its own path and, while waiting to receive a name from its future owner, suggests a further reflection on the possible bond between the two species, human and animal.

Giovanna Dalla Chiesa observes: “With the thread of her ’embroidery drawings’ on transparent paper, Alice Schivardi has not only told stories that bring to the forefront the intimacy and focused contemplation of the feminine world, but has also built a bridge between aspects of artistic representation that have traditionally remained abstracted from reality and those deeply rooted in life.

These include not only ethically or spiritually exemplary figures such as the partisan Mario Fiorentini or Saint Rita of Cascia—protagonists of some remarkable performances—but also the entire living world: from extraordinary social insects like bees to other creatures who, regardless of their place in the natural order, deserve respect, even to the point of receiving a proper burial. This extends to the animal kingdom of dogs and birds, with whom the artist achieves a profound sense of identification, as well as to the broader spectrum of human diversity—ethnic, gender-based, or genetic—as reflected in her recent work with the blind.

Alice Schivardi’s thread is, therefore, a thread of thought—immaterial yet persistent—that weaves both severe and gentle stories onto transparent surfaces, allowing it to float in the air. It crosses boundaries, continually forging connections and, when necessary, reshaping the narrative to reunite what human prejudice has divided.

This wise and profound thread, aesthetically enchanting, engages with anthropological, political, social, and religious dimensions—foundations of our human awareness and essential to the possibility and necessity of harmonious coexistence and survival.”

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

The Adventures Of Alice

By Giovanna Dalla Chiesa

THE LIGHT

I still carry the impression of the light that surrounded me when I first entered Alice Schivardi’s studio. Nothing I observed afterward can compare to the effect of that milky, enveloping light, which evoked for me certain misty mornings in the snow-covered high mountains, when the radiance of the light is at its peak.

By chance, I recently heard Alice Schivardi describe her need to offer, through her work, a restorative breath against the cynicism of a world devoid of hope and humanity—much like the one we live in: ‘breath of light”. No definition seemed more appropriate to capture the profound essence of her intents.

Alice Schivardi’s work, as diligent as that of a busy bee, pierces the air with a needle through paper—not only to draw nectar and capture the tender substance of fleeting moments, as bees do, but also to defend values with her sting or to signal the dramatic essence of human existence. To deepen her understanding of the behavior of bees, the artist even took beekeeping courses.

Since her thesis on Louise Bourgeois at the Brera Academy in 2004—incorporating quotes and opinions gathered from others in order to turn it into a collective event—Alice has shown a tendency to share her own experiences with friends, family, and even strangers, inviting other perspectives to enrich and expand the meaning of her work. She was quickly labeled a relational artist. But how does her relationality express itself? Alice’s work carries the essence of folk tales and fairy tales, along with the sophisticated elegance of an elusive, yet concrete and ever-present, quintessential form.

What happens between the light drawing that her hand places on the tracing paper and the thread that follows its path is a subtle shift—a fraction of space that moves the action to the periphery, leaving a trail of light in its wake. This is how the threshold of our perception expands, spreading that gesture in the air like an echo, a halo that accompanies its journey.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite” wrote William Blake in a famous passage that opens to an infinite space-time extension. And this is what it is about—overcoming boundaries, opening up broader horizons to our ego, trapped within its own walls, where the gaze can expand to sense the extraordinary unity of all things, from the smallest to the largest, which we are only allowed to imagine, but that, in itself, is already quite something. That double mark of the hand opens up a parallel universe for us. The images in Alice’s stories are often framed by ovals, a way of cradling them in a womb—the egg—and not merely enclosing them, seemingly, in frames like 19th-century miniatures. They are figures woven from an intrapsychic fabric—naturally so, because before venturing out, one must first gather within oneself—suspended in the shifts of memory, as if immersed in the amniotic fluid of a prenatal dimension, that of not yet being, lingering in the paradise we knew in the womb or just outside, when every gesture is an act of protection and welcome into the world we’ve just entered, reassuring that the love that generated us will never abandon us.

THE THREAD

In 2008, while preparing her works for the “Welcome Remembering” exhibition at the American Academy in Rome, Alice, almost by chance, notices a needle and thread in a corner of her studio. She decides to incorporate them into her transparent paper drawings, and in a flash, she realizes that the thread could serve as a bridge to everything.

This marks her first plunge into the reality of those stories that form the original substratum of her work. But in order to tell them, it is necessary to live them —crossing countless boundaries, confronting fears, mistakes, and limitations, and constantly putting oneself to the test. Each new experience profoundly transforms the artist, and at the same time, reshapes the conditions in which her work is born and evolves.

Opportunities begin to multiply. In 2012, the “Coccinelle” (“Ladybugs”) series takes shape—a collection of 32 delicate, miniature ovals that encapsulate fragments of intimate life, weaving personal and family stories capable of evoking deep emotions. The works will be exhibited in 2013 in the “Genius Loci” exhibition in Pesaro, curated by Ludovico Pratesi and Paola Ugolini, and in 2015 at Richard Saltoun Gallery in London, curated by Paola Ugolini.

In 2012, she also holds her first complex solo exhibition at The Gallery Apart in Rome. She assigns six people, varying in age, gender, and personal background, the task of sharing a personal story. The stories are recorded onto magnetic tape and played through six different speakers scattered throughout the gallery. Meanwhile, a 12-meter acetate sheet, titled “Ad immagine e somiglianza” (“In Image and Likeness”), unfolds a narrative composed of drawings and embroidery, inspired by the dramatic stories shared during the encounter, all preserved in anonymity. The title “Equazione Uno” (“Equation One”), refers to the way waves propagate in physics. Upon entering, the audience is enveloped in a chaos of overlapping voices. Only by approaching the sound source—a pure sinusoidal tone for each story, created by composer Giacomo Del Colle Lauri Volpi—can one distinctly hear each individual narrative. The intertwining of the collective and the individual, with a focus on the intimacy of storytelling, aims to create a space where everyone can recognize themselves in the experiences of others, fostering a collective identity as a shared heritage.

VIDEO, PERFORMANCE, PHOTOGRAPHY

In 2014, she is selected for an artist residency by the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York, in collaboration with the museum dedicated to preserving Hispanic-American traditions in Brooklyn (El Museo de Los Sures). She creates two distinct works.

The first, “Wormholes”, alludes to the topological structures that, according to the theory of general relativity, could hypothetically connect disparate points scattered in space and time. Alice Schivardi engages the local community, encouraging them to share their personal sentimental stories. Then, with the help of Korean sound engineer Kwang Hoon Han and woodworker Richard Lee, she manages to build a wall with hidden speakers, which can only be heard by approaching the sound sources, like a sort of giant confessional.

The second work, “Yellow”, is a video in which she explores a different concept: a form of “identity transfer”. She entrusts the ethereal element of air with the sound of her own name, spoken aloud by young strangers of different nationalities. The result is both amusing and thought-provoking, as each individual struggles to pronounce the letters of her name, creating a further shift from the material realm of her physical presence to an immaterial, shared experience.

While in Rome, at an Internet café on Tiburtina Street, she developes a strong bond with the Bangladeshi family running the business. This encounter led to a project that she immediately recognized as having limitless potential— “Ero figlia unica – Tutti con me e me con voi” (“I Was an Only Child – All with Me and Me with You”), a paradox that addresses the increasingly relevant themes of cultural and ethnic identity, as well as the deconstruction of the traditional family model. The series would grow significantly over time.

Thanks to her ability to build deep human connections—despite differences and prejudices—she gradually immerses herself in the daily life of a family unit, eventually transforming into one of its members. Through her behavior, clothing, and makeup, she underwent a complete metamorphosis, gaining full acceptance within the group. The final photograph seals with its presence the truth of a slow process of transformation, that is not merely external, but, on the contrary, especially internal. In 2015, “Ero figlia unica” also became the title of the exhibition curated by Ludovico Pratesi and Paola Ugolini at the Pescheria Foundation in Pesaro. Alongside the previously described series, a sequence of 14 new large works, drawn from the New York video “Yellow”, was added in the expansive Loggia, which, thanks to a large window, can also be observed from the outside. The number 14 corresponds to the letters of her name, each represented by an open mouth captured in the act of pronouncing its syllables. In this occasion, the first insect to be placed near the lips appears: a stag beetle, to which the artist attributes a propitious character. That same year, she also establishes a strong partnership with Matteo Boetti, who hosts her solo exhibition of drawings and embroidery, “Così sia” (“So Be It”) at his space in Todi.

Already with “Ero figlia unica”, Alice realizes that to fully embrace performance as a medium, she could no longer avoid direct physical engagement.

Her beloved pomeranian dog, Blanco—which had already inspired the photographic work “La Madonna del Volpino” (“The Madonna of the Pomeranian”) during her thesis – passed away in 2014. The artist decides to collect its fur and craft it into a garment, which she would wear as a second skin, imitating its poses until she completely identifies with the animal. This process gave rise to a series of photographs and bestiaries in which “Blanco, the non-existent animal” undergoes continuous metamorphoses, even sprouting wings.

Her work, deeply influenced by her nomadic temperament, also reveals a keen interest in environmental and ecological themes (series “Cimitero per insetti”, 2008-2018) (“Insect Cemetery”) as well as the concept of flight.

In May 2019, Alice Schivardi had the opportunity to meet a group of ornithologists working along the Lazio coast, in the Torre Flavia Nature Monument (Ladispoli). This site is home to the fratino (Kentish plover), an endangered species. In collaboration with street artist Claudio Montuori—specialized in reproducing bird sounds—and with the support of the artQ13 Association, Alice engaged in an in-depth study of the birds’ behavior. This research culminated in an extraordinary performance, “A suon di ali”, in which Montuori, dresses as a “birdman,” and Schivardi together interpreted all aspects of the fratino’s courtship ritual. Accompanied by the sound of musical instruments created specifically for the occasion, Alice performed wearing a feathered dress she had sewn herself, merging the human and animal worlds into a moment of deep symbiosis.

In the fall of the same year, as part of Giuliana Benassi’s project dedicated to the historical transformations of the Campo de’ Fiori area in Rome, after meeting Mario Fiorentini, the former partisan who was over a century old at the time, Alice decided to reenact his anti-fascist action, faithfully retracing his route on a vintage bicycle. This work was later displayed in the showcase at Via del Consolato 12, as part of the “The Independent” project by the MAXXI Foundation.

Among her most significant recent performances and workshops is “Corvi o Colombe?” (“Crows or Doves?”), a special project curated by Valentina Ciarallo, presented during the Art Fair at the Nuvola by Fuksas in Rome. The performance, depicting the struggle between good and evil, involved four additional actors alongside the artist and extended across all three levels of the Nuvola, captivating audiences with its extraordinary involvement and success. Additionally, there is the tactile workshop for blind people, “The Thread That Binds Us,” in collaboration with “Dispositivi Comunicanti” and “U.I.C.I. Roma,” held at Alvéus Studio in Rome.

UNLIMITED

Perhaps the awareness of Yves Klein’s famous action on “flight,” or the discovery that bees—according to legend— entered and exited the mouth of Saint Rita without stinging her, as well as Klein’s own devotion to the saint, inspired Alice Schivardi’s pilgrimage on foot, “Ad-usum/peregrinorum”, to Saint Rita’s house in Roccaporena di Cascia. There, in the summer of 2020, she participates in a residency invited by Franco Troiani, to prepare a series of actions and performances still under development and in progress.

This experience, intertwined with the forced isolation of the pandemic lockdown—and the profound need for regeneration it entailed—led to the creation of a drawing later featured in Vogue Italia as part of an editorial series of covers by 49 artists. The image depicts a bee landing on a young girl’s mouth, highlighting the threshold between inside and outside, and evoking the suspension between word and silence. A powerful and enigmatic emblem, it acts as a concealed seal, conferring an almost sacred and inviolable form upon countless possible interpretations.

Throughout Alice Schivardi’s practice, the immediacy of certain gestures and intuitions is counterbalanced by the slow pace of reflection, research, and study—an open-ended process that unfolds across both time and space.

Her art, radiant with light, naturally seeks to transcend enclosed spaces—not only because it refuses to remain on the surface, but because it digs deeper, revealing invisible channels of connection between things, much like the unseen ways in which life itself establishes contact, relates, reproduces, and regenerates. This is how nature expresses itself: by following the simplest path to overcome apparent boundaries, just as ecology teaches us—and just as Alice does, intertwining languages without ever losing the thread of discourse.

A few years ago, the renowned geneticist and physicist Edoardo Boncinelli observed that the DNA of a midge is far more similar to that of a human than one might expect.

Alice is acutely aware of the invisible relationships that bind us, just as she is of the visible world and her own private life. Her grandmother left her a message that has never faded from memory: “nel mio ricordo il filo ci unisce” (“In my memory, the thread connects us”). Alice’s thread is, perhaps, the thread of thought—a logos that, in its immaterial nature, infiltrates everything, connecting even seemingly distant realities that, upon closer examination, reveal strikingly similar behaviors.

This thread, both wise and aesthetic, extends across anthropological, political, social, and religious dimensions—the very foundations of human awareness, and the basis for the possibility and necessity of harmonious coexistence and survival.

Ancient sources, moreover, tell that bees landed on the lips of Pindar, Plato, and Sophocles to bestow upon them the gift of speech and persuasion.

The work of the artist, poet, and philosopher is like that of bees, which, from the superficial and perishable beauty of a flower, manage to extract nectar capable of acting much deeper, with the perpetual nourishment of thought and culture: an Opus Magnum to which everyone should strive.