The exhibition is the third and final in a series of three—“When Thread, Color, and Word Intertwine”—curated by Giovanna Dalla Chiesa, which brings together the work of three artists: Alice Schivardi, Luciana Pretta, and Luisa Lanarca.

On view is a selection of tapestries by Luisa Lanarca, created between 1980 and the present using the two-shaft weaving technique, enriched with mixed media interventions carried out during the weaving process.

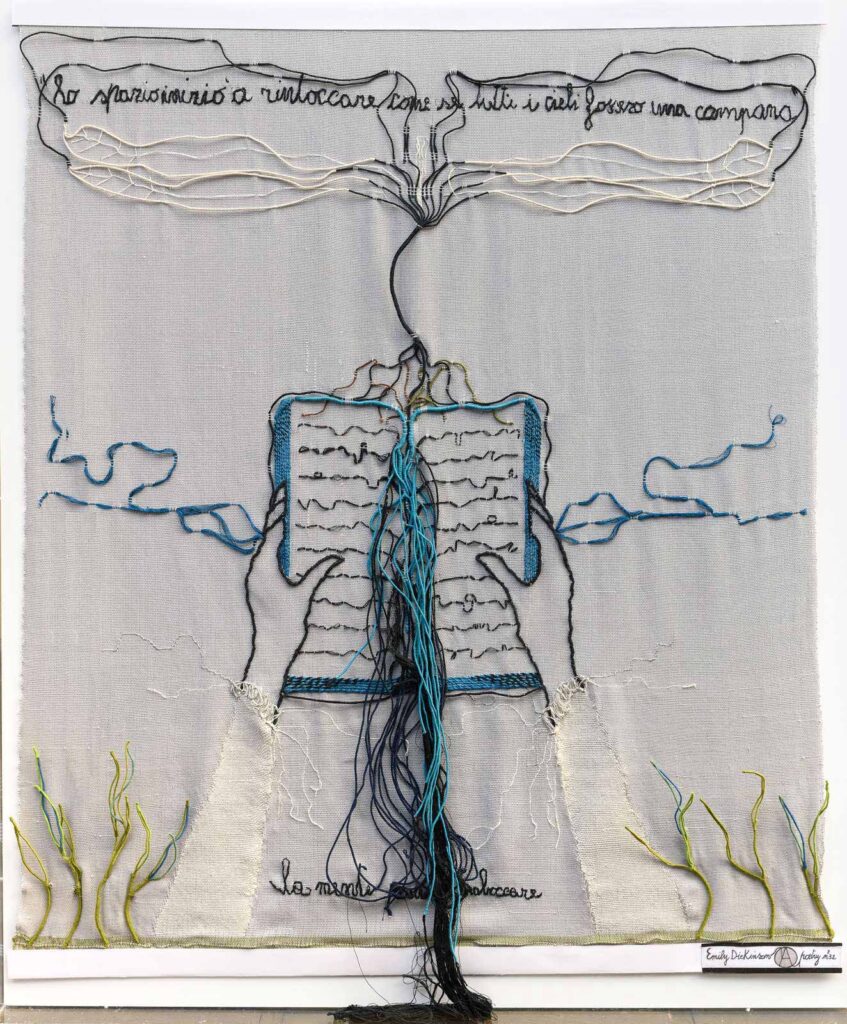

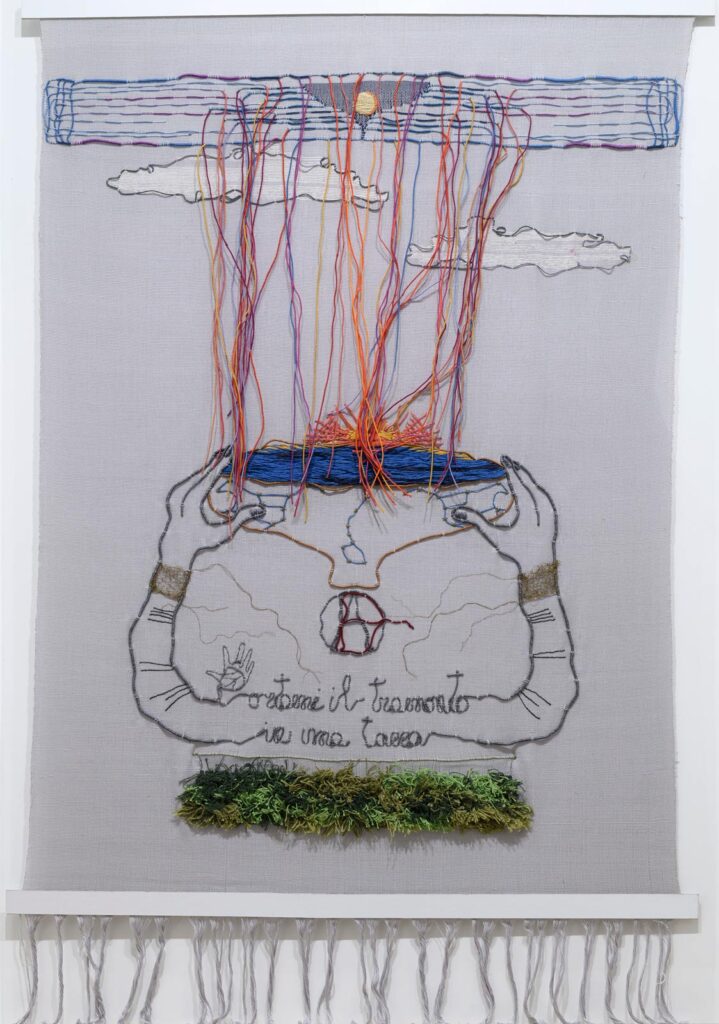

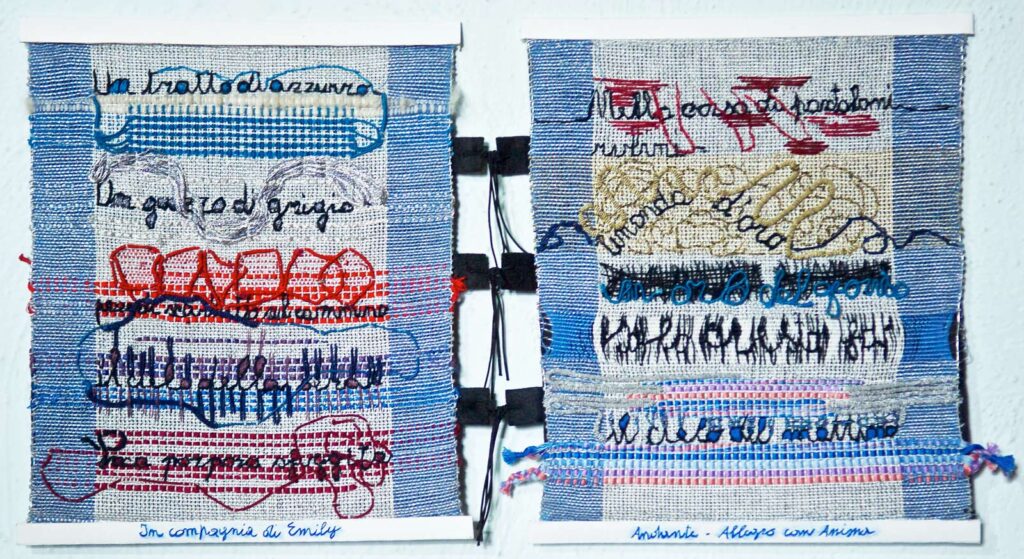

These works are the result of a creative journey that intertwines direct experience of the material with a theoretical exploration based on studies of Visual Perception and Gestalt, revealing a deeply layered exploration. In some pieces, inspired by the poetry of Emily Dickinson, thread, color, and light merge with poetic language, surfacing in the woven fabric and turning it into an invocation, evoking the signs and affiches of the late 19th century.

As Giovanna Dalla Chiesa observes: “Weaving is part of the most complex faculty of human thought, tied to a destiny not of separation, but of integration between the paired elements nature has given to human beings—arms, legs, eyes, nostrils, ears, and, above all, the two cerebral hemispheres. This integration creates the conditions for a new being to emerge, a work that, in turn, will gradually shape its own fate.

Luisa Lanarca did not come to weaving later in life, but rather embraced it from the outset, studying under renowned masters such as Laura Marcucci Cambellotti and her Textile Workshop. What makes her journey exceptional is her analytical approach to it on a psychological level, thanks to her studies in Visual Perception and Gestalt, which she pursued at the Luigi Veronesi School in Milan.

Unlike many, weaving has allowed Luisa Lanarca, in her unique journey, to cultivate self-knowledge, aligning with the sharpening of her own identity, while also embarking on a journey into language, where poetry becomes a space of liberation, emotion, and fullness. According to the artist, the intertwining of reason and feeling, of eros and psyche, can only find its resolution in a synthesis of laboriousness that resembles a silent prayer, illuminated by a light that transcends all boundaries—like poetic words, and in particular, those of Emily Dickinson, capable of giving voice to her silence.”

Selected works

Gallery

Critical essay

Weaving in Psychological and Poetic Modes

By Giovanna Dalla Chiesa

Fila, fila ortolanela,

fin che gira la molinela,

fila, fila ortolanela,

fin che ‘l fuso l’è terminà

(Ancient song from the Val Lagarina)

Spin, spin little ortolan,

until the little wheel turns,

spin, spin little ortolan,

until the spindle is finished

Weaving, an activity that dates back to the Neolithic period because humanity could not do without covering itself, has been experiencing a remarkable resurgence in the art world for over a decade, particularly due to the way many female artists are embracing it. Despite having little to do with the traditional technique, they are adopting this form of expression, which has become especially popular today.

Those with a true mastery of the subject may even risk being considered outdated or unaware of the new possibilities and innovations with which this ancient method is now being practiced and reimagined beyond its traditional boundaries. In this regard, Luisa Lanarca stood out to me as a remarkable exception.

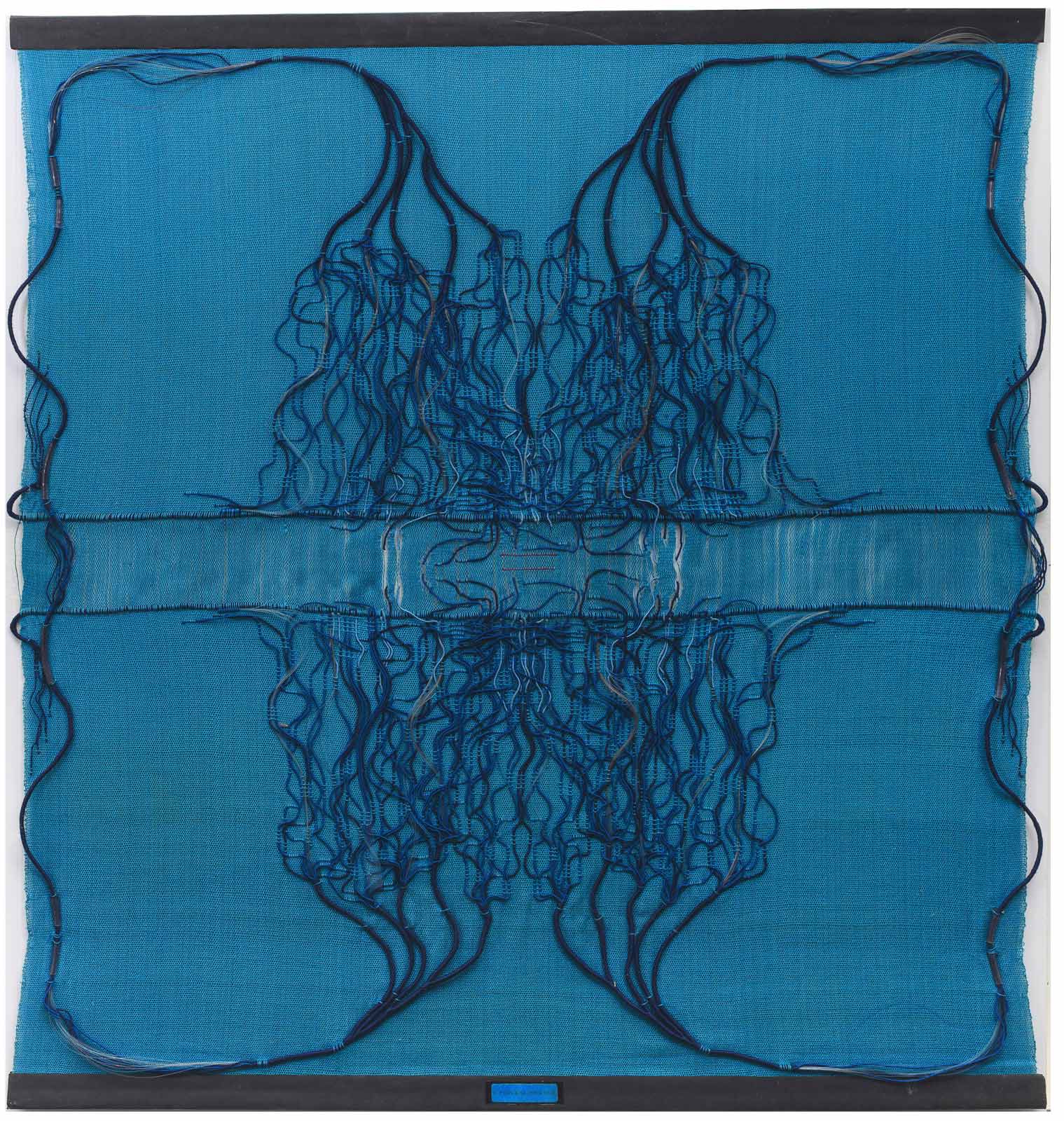

Although rooted in a well-defined tradition and trained since the 1970s, her approach to weaving differs greatly from the traditional, artisanal aspects of the medium, despite her deep knowledge of them. Her restrained use of color, mainly monochrome, the absence of a strong material focus in her compositions, and her practice of enclosing her works in plexiglass cases, which lends them a sense of preciousness, all contribute to giving her pieces an inherently conceptual character, with a freshness due to her innovative approach.

Thus, I wouldn’t define Luisa’s works by their technique – like tapestries, for example – even though the method is important. Rather, I regard them simply as works of art, beyond any technical classification, because it’s clear that the artist, with her perspective, goes beyond technique. “I would like my works to provide material for reflection and awaken feelings in those who contemplate them,” she explained.

THE STUDIES

After her practice at the Textile Workshop in Rome under the exemplary guidance of Laura Marcucci Cambellotti, Luisa moved to Milan to attend Luigi Veronesi’s school. He was a paragon of versatility, known both for his strictly abstract painting – of which he was a pioneer and theorist – and for his work in photography, direction, and scenography. He was also a master of color theory, which he dreamed of aligning with sound.

This environment fostered an openness to exploring different genres and their possible interrelations within the technical realm. Alongside him worked a Gestalt specialist, who introduced her to the essential concepts of the Psychology of Vision. This environment proved invaluable, offering key insights that broadened her understanding and deepened her connection with her inner self. As the artist explained: “In my work, I have never subscribed to traditional dogmas. I’ve always believed that creativity, specific intentions, and even techniques are the result of visual training and research, which gradually take shape as we strive to comprehend the world around us. For instance, by observing nature, one can study the intricate weavings of bird nests, butterfly wings, the intertwining of branches, or the network of veins carrying sap in leaves and flower petals. Of course, like in any form of work, a technical foundation is essential, but it is the strength of imagination that ultimately guides how to play with threads, colors, and various materials.”

For years, Luisa Lanarca devoted herself to intensive teaching, convinced that the educational and pedagogical aspects of weaving, once introduced in schools, could offer great benefits for shaping new awareness. She did this particularly by collaborating with municipalities and regions in Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany. Weaving provided her with a means of self-connection, an experience that became inseparable from her identity. The slowness of the medium inspired deep reflection and, alongside reading, accompanied her daily life, filling the emptiness of a solitude she both sought and endured. For this reason, despite engaging in other artistic endeavors – such as photography, several cycles of surrealist watercolors, and drawing, in which she particularly excels – she has always returned to this practice, her most cherished, which truly represents her.

THE WORK

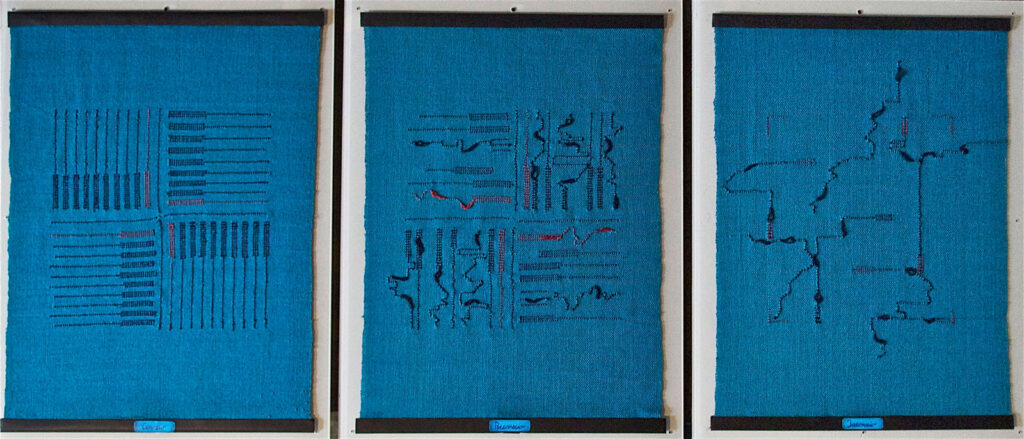

The oldest work in this exhibition is the small-format triptych from 1982, Conscio – Preconscio – Inconscio (Conscious – Preconscious – Unconscious), where her studies on perception are elegantly applied: the conscious is represented by a quadripartite and orderly composition of lines in a simple yet highly effective graphic arrangement; the preconscious is characterized by more intertwined, electric, and open paths; and the unconscious carries a highly distinctive imprint that, unusually, seems to anticipate the internal structures of a computer, still years away from being developed.

More complex and larger in size, allowing for a fully immersive viewing experience, is the triptych Autismo – Estroversione – Nevrosi (Autism – Extroversion – Neurosis).

Here, the dynamism of the marks begins to surpass the composition: in Autismo, the lines are confined within themselves; in Estroversione, they expand towards the center, forming a transparent square of striking effectiveness, designed to channel swirling, energetic patterns towards the periphery, leaning towards a floral evolution. In Nevrosi, it presents a sparse arrangement of lines, without clear direction, unable to find its own purpose. The marks, taken as a whole, already appear alive and sensitive, resembling nerve filaments.

THE BODY OF LIGHT-COLOR

In 1987, with the triptych Voyeur, there is a decisive leap. In each piece, a mark delineates the entire background weave, embracing its area of action, and opens towards the center. This void is capable of transmitting a strong energy, projecting into the movements and rendering of all the warp threads. It is as if one is seeing through the weave, perceiving “among the branches of the forest,” the clearing of light that Heidegger – and, following him, Maria Zambrano – referred to as Lichtung. A pure language of signs, lines, and color to be contemplated in silence, rich with luminous inner tension but wordless.

What is primarily emphasized is the design, the idea, rather than the fabric structure – an idea that seems to emanate from the body like a light twist of smoke. The sign, in osmosis, breathes life because it has been freed from the constraints of a predetermined direction, becoming mobile and responsive to the fluctuations of the energetic field the artist has identified. It is about channeling psychic energies and allowing their potential to be felt, a potential that will speak to each viewer in a unique way, depending on their sensitivity.

A sense of peace and rest envelops the viewer who stands before one of these blue surfaces, often arranged by the artist in sequences of three – thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, as in triptychs. And if, rather than pausing, one chooses to move through the space, it feels like a gentle navigation, gliding effortlessly without encountering obstacles. This blue has a presence that welcomes and absorbs like water. It doesn’t have the transparent clarity of the sky; its indefinable tone, reminiscent of certain mountain lakes, is pearlescent with a touch of gray, where nylon threads intertwine. Even the plexiglas casings, reflecting our figures, keep them suspended in fluidity. According to Plotinus, the body must maintain alignment with the soul and ensure they do not drift apart. In fact, if the body moves in straight lines, the soul – which is more accurately referred to by its Greek term psyché, as this is what it truly is – strives to move always toward itself, in a circular motion of consciousness, reflection, and life that returns to itself. The constant fine-tuning required for this purpose are very similar to a sailor’s course corrections while navigating, but weaving is also one of the most intricate and complex ways humans have devised to integrate parts that nature intended to be separate: two arms, two legs, two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, and even two brain hemispheres – not to keep them apart, but to establish relationships from which new creation can arise, a work that gradually shapes its own destiny.

Luisa knows this very well.

THE WORD

I do not know how or when the encounter between Emily Dickinson’s verses and Luisa Lanarca’s feelings occurred.

Her friendships with writers Perla Cacciaguerra, Mimma Pisani, Adele Cambrìa, and Elena Gianini Belotti may have prepared the ground.

The word had already surfaced in Luisa’s mind, though she had chosen not to speak it, leaving it unconscious in a dense tangle of signs, almost like a murmur or noise in the reversed dialogue of amusing characters: two Neapolitan coffee pots.

What is certain is that the impact on a temperament used to suppressing its emotions and disguising its feelings was profound. Nothing expresses this better than the verses the artist, after months of work, chose to inscribe in their entirety in two of her major works created between 2024 and 2025.

Lo spazio cominciò a rintoccare come se tutti i cieli fossero una campana. La mente parve traboccare (The space began to toll as if all the heavens were a bell. The mind seemed to overflow).

One could not be more explicit: it is a revelation, charged with all the turmoil that such an experience entails.

Portami il tramonto in una tazza (Bring me the sunset in a cup): an invocation that springs from the innermost fibers of being.

Where the order of our rational language breaks down, opposition ceases, and the word finds its vital meaning again, its liberation, and fullness.

Luisa Lanarca has chosen that, here, the thread is no longer ‘the thread of discourse’ – the logos – but rather the reuniting of being, which embraces even the irrational in a surge that resonates with the longing to live and to open oneself to the grace of nature and the cosmos. Here, we find the synthesis between the laboriousness of weaving – akin to the silent prayer that binds the universe together – and the light of love, capable of transcending all boundaries. And Emily Dickinson’s poetic voice, in whose reclusive life Luisa Lanarca’s own seems to find a reflection, appears to redeem all of her silence.